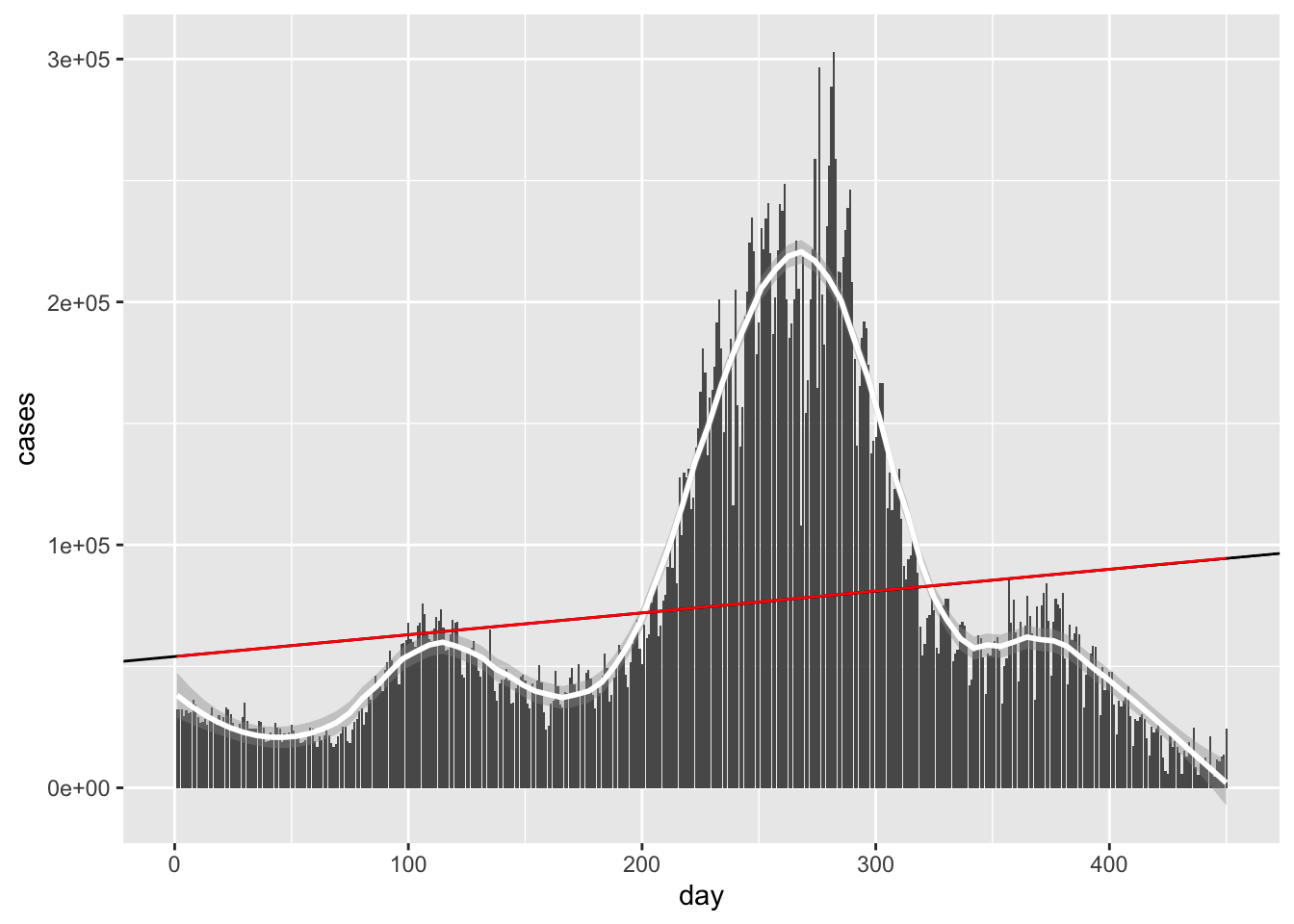

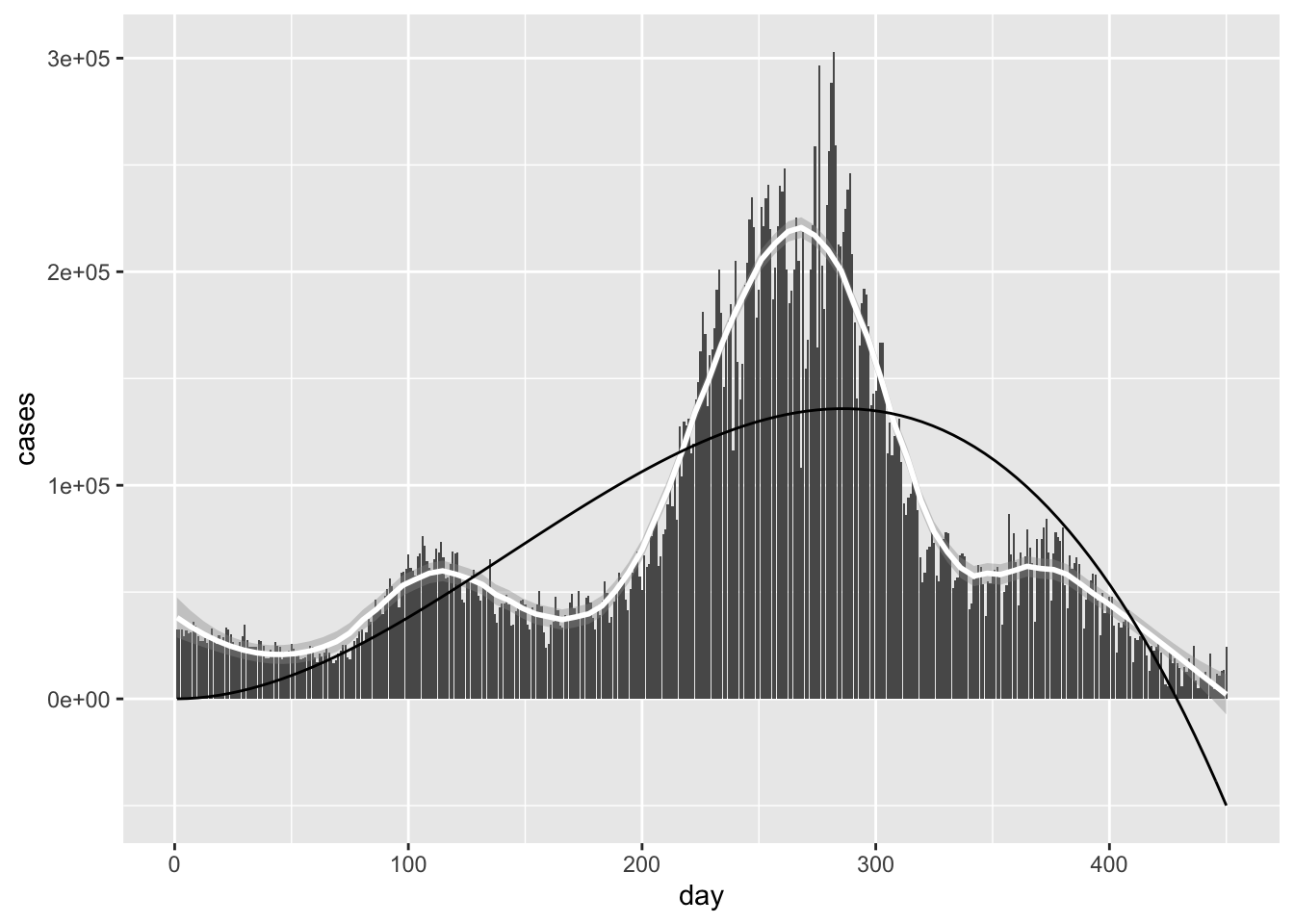

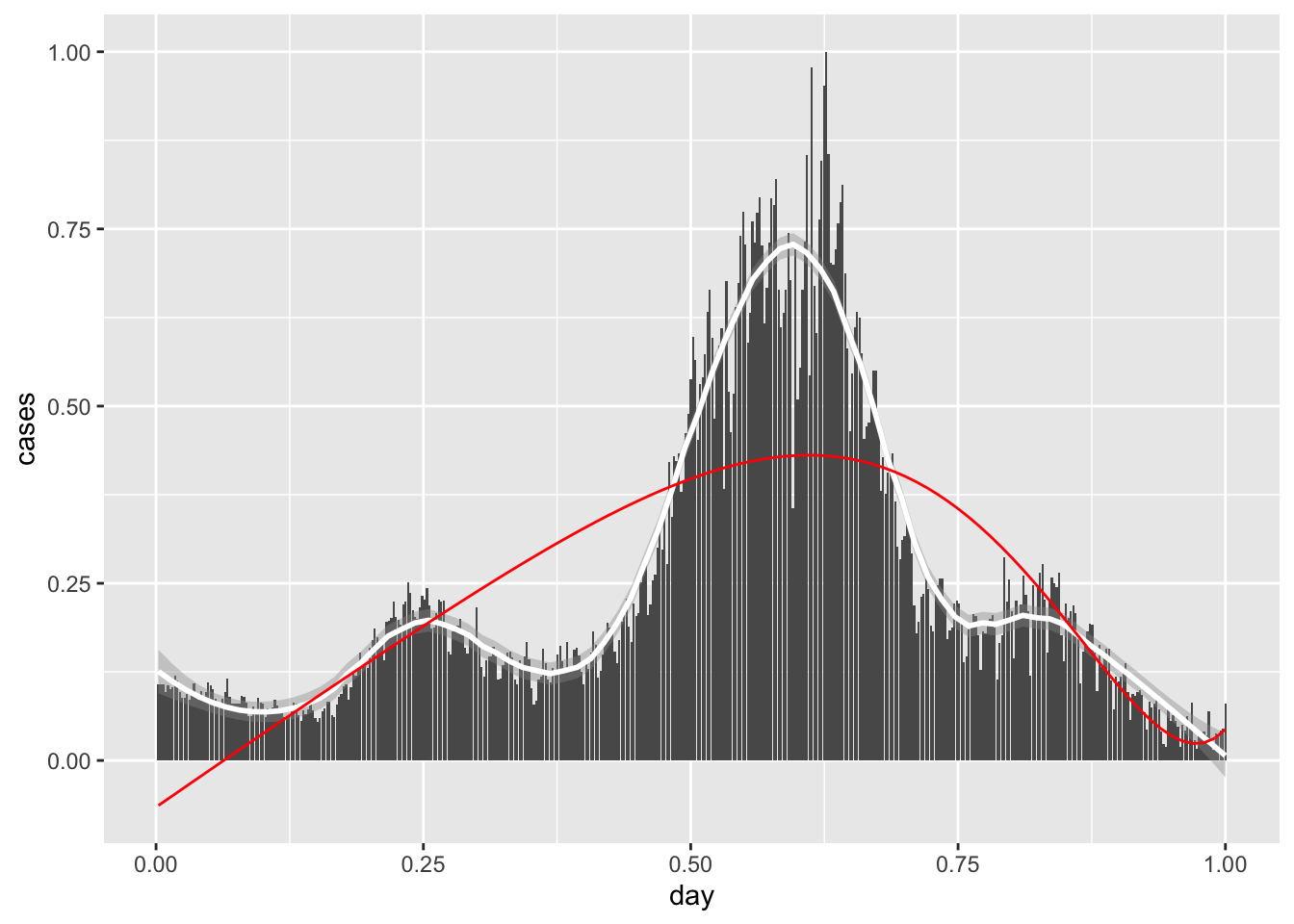

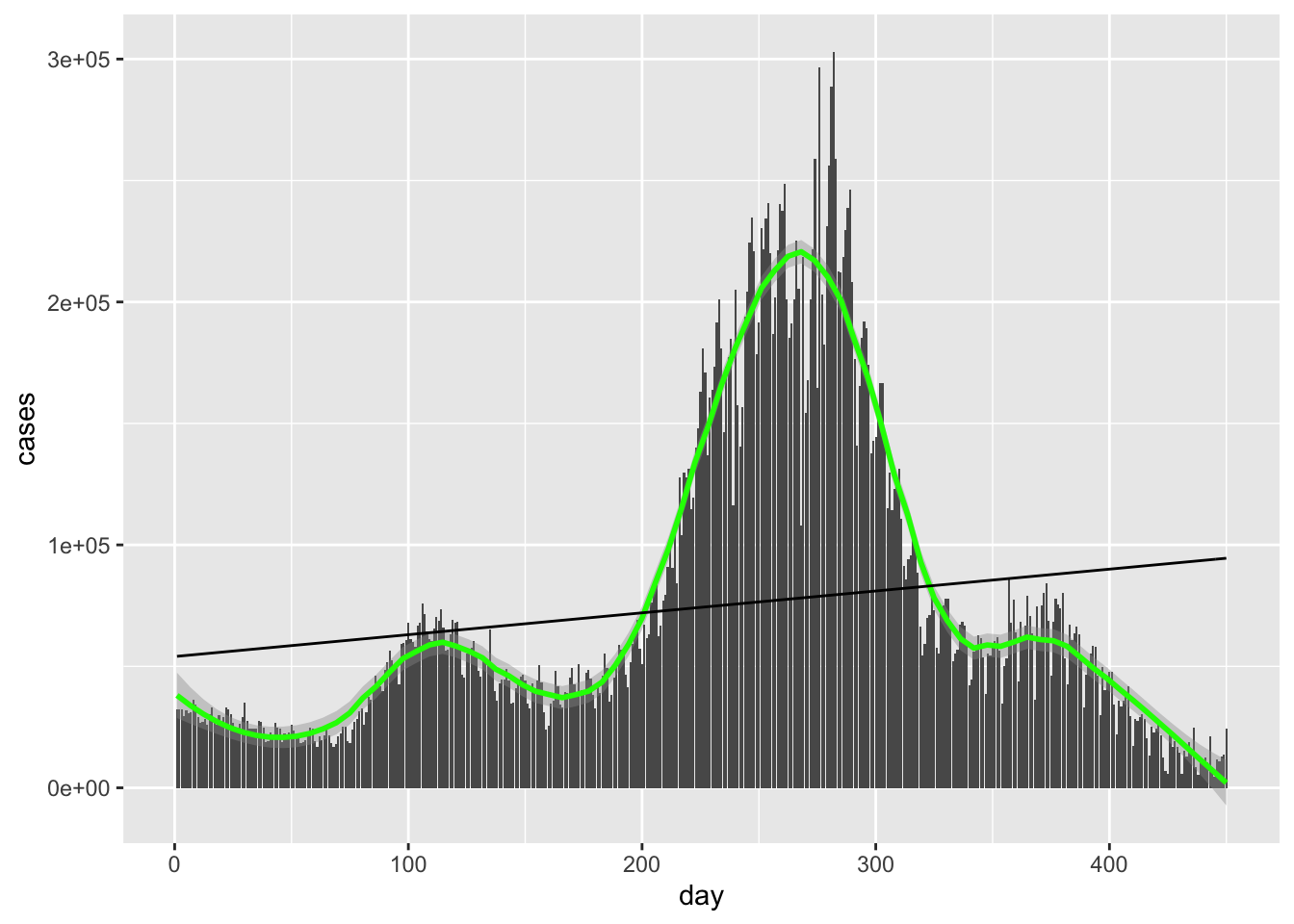

- 1 An example with tracking coronavirus cases

- 2 Local regression

Regression and its many forms

This lab will be focused on the many ways to perform

regression on single variable data. From the previous

notes, we learned about linear regression. For a

dataset {(x1,y1),…,(xn,yn)}, linear regression uses the linear model of y=α+βx,α=ˉy−ρsysxˉx,β=ρsysx.

where we use the correlation coefficient

ρX,Y=∑(xi−ˉx)(yi−ˉy)√∑(xi−ˉx)2√∑(xi−ˉx)2

Recall that ρ gives us a measure of the linear relationship between input and output. For nonlinear relations (parabolas, circles, etc.), the correlation coefficient will not be as effective (you may even get something near 0!). The terms ˉx,ˉy are means of the input and output, respectively, and sx,sy their sample standard deviations.

Let’s take a quick look at some more subtle points regarding correlation and linear regression.

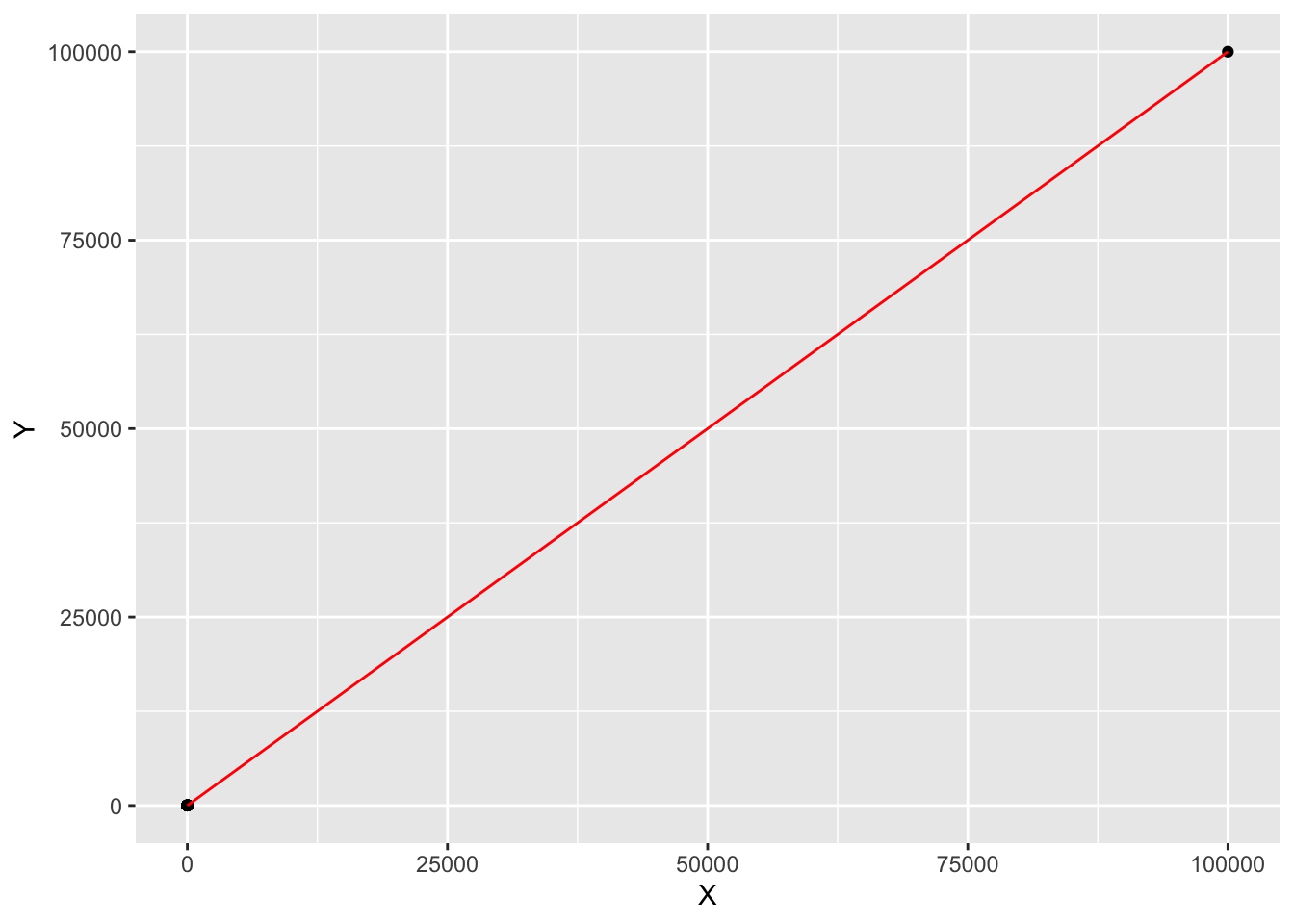

0.1 Corrupting ρ with a single point

Unfortunately, correlations and linear fits are sensitive to outliers. To see this, let’s make some noise!1 By this, generate independent samples of input and output.

X = runif(100)

Y = runif(100)

cor(X,Y)## [1] 0.1051301Q: Shouldn’t we be expecting exactly 0 as an answer? Why or why not?

By adding a single point, we can boost our correlation to be as near to 1 as we wish.

X[101] = 10^5

Y[101] = 10^5

cor(X,Y)## [1] 1What on earth is going on? How can one point mess things up so much? Looking at the formula for ρ can help. For the augmented dataset

x={x1,…,xn,xbig},x={y1,…,yn,ybig},

Q: Compute the big terms in the numerator and denominator in the formula for the correlation coefficient. In the numerator, you should be looking for terms containing xbig∗ybig, and in the denominator, you should be looking for terms x2big and y2big. Can you find these terms and show that their ratio approaches 1 for large positive values of xbig and ybig?

Without doing the asymptotics of the previous question, we can get a visual of what our line should look like. Let’s plot our points and the line of best fit.

rho = cor(X,Y)

sx = sd(X)

sy = sd(Y)

xbar = mean(X)

ybar = mean(Y)

riggeddata = data.frame(X,Y)

linefit = function(x){

alpha = ybar- rho*(sy/sx)*xbar

beta = rho*(sy/sx)

return (alpha + beta*x)}

riggeddata %>% ggplot(aes(X,Y)) + geom_point()+stat_function(fun = linefit, col = 'red')

The other 100 points are so scrunched that they appear to be a single point in this graph. This graph, in a sense, is zooming out, and from this perspective, the line of best fit seems to do a pretty good job. Recall that correlations are invariant under affine transmations x↦ax+b, so the scaling in the X and Y variables doesn’t really matter when looking at something like a correlation.

0.2 (X vs. Y) vs. (Y vs. X)

One nice property about the correlation coefficient is that it is symmetric, meaning that ρ(x,y)=ρ(y,x).

Q: Can you deduce that ρ is symmetric by looking at its formula?

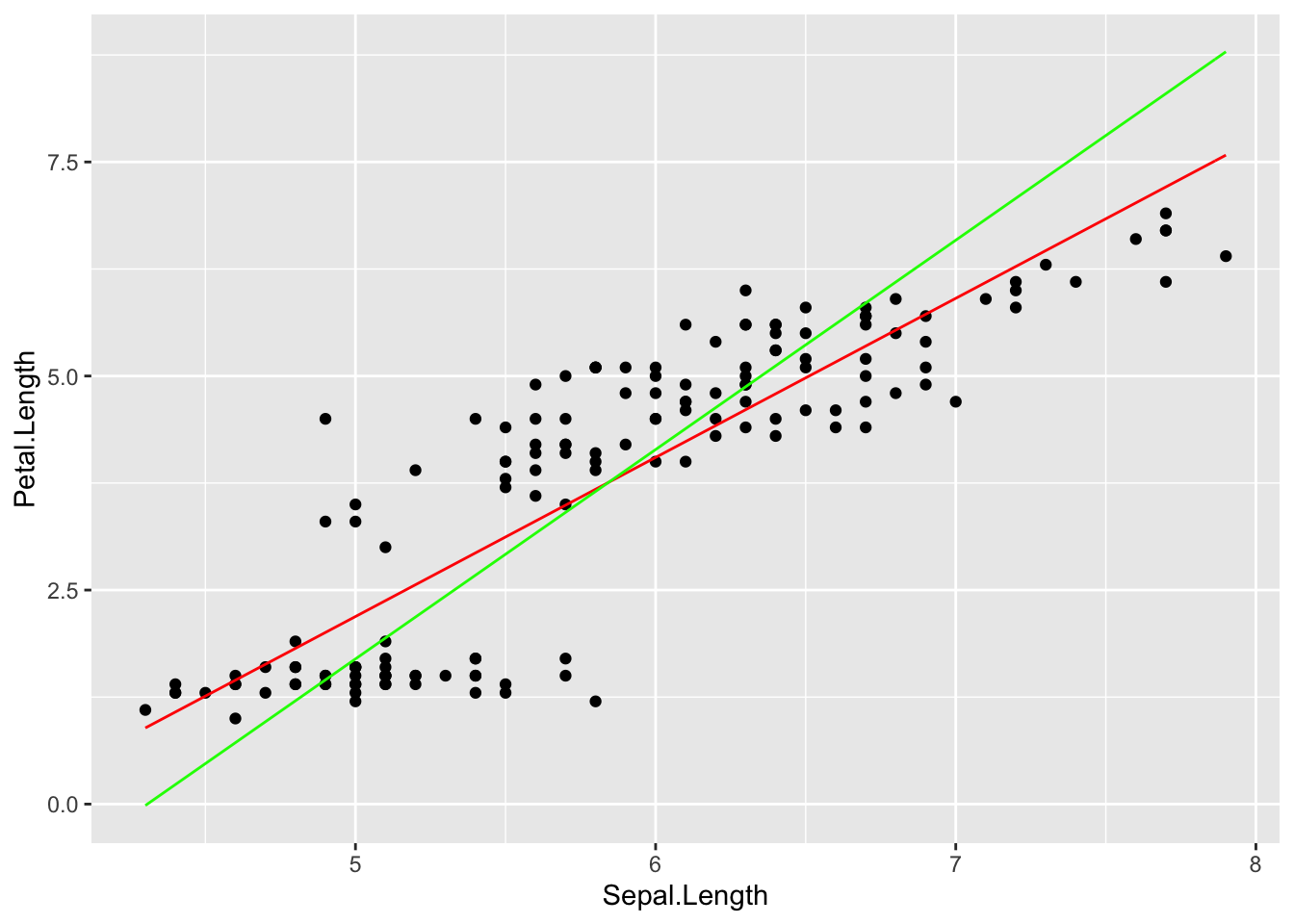

Despite ρ being symmetric, we

have the curious fact that the line of best fit for Y given X is in general not the same as the line

for X given Y. To see this, let’s use our trusty

<

X = iris$Sepal.Length

Y = iris$Petal.Length

rho = cor(X,Y)

sx = sd(X)

sy = sd(Y)

xbar = mean(X)

ybar = mean(Y)

linefit = function(x){

alpha = ybar- rho*(sy/sx)*xbar

beta = rho*(sy/sx)

return((alpha + beta*x))

}

#Now computing the line of best fit for X given Y:

rho = cor(Y,X)

fliplinefit= function(x){

alpha = xbar- rho*(sx/sy)*ybar

beta = rho*(sx/sy)

return((x-alpha)/beta)

}

iris %>% ggplot(aes(Sepal.Length, Petal.Length)) +

geom_point()+stat_function(fun = linefit, col = 'red')+

stat_function(fun = fliplinefit, col = 'green')

The main point here is that switching arguments produces two separate optimization problems. In the graph above, the red line is minimizing vertical residuals, whereas the green line minimizes horizontal residuals.

#Polynomial regression

We can easily generalize linear regression to cover the class of

polynomials, those functions which take the form βNxd+βN−1xN−1+⋯+β1x+β0=N∑i=0βixi

the variable N is called the degree of the polynomial, and is the highest power that we take of the independent variable x. For fitting a degree N polynomial to a dataset, our task is to determine the best possible values for the N+1 coefficients β0,…,βN. We can express this as the optimization problem

(ˆβ0,…,ˆβN)=argmin(β0,…,βd)d∑i=1(y(ˆxi)−ˆyi)2=argmin(β0,…,βN)d∑i=1(N∑i=0βiˆxi−ˆyi)2.

The argmin tells you to find values of (ˆβ0,…,ˆβN) that

produce a minimum root mean squared error RMSE=√d∑i=1(y(ˆxi)−ˆyi)2/d

These are the constants you will use to plot your polynomial of best fit.

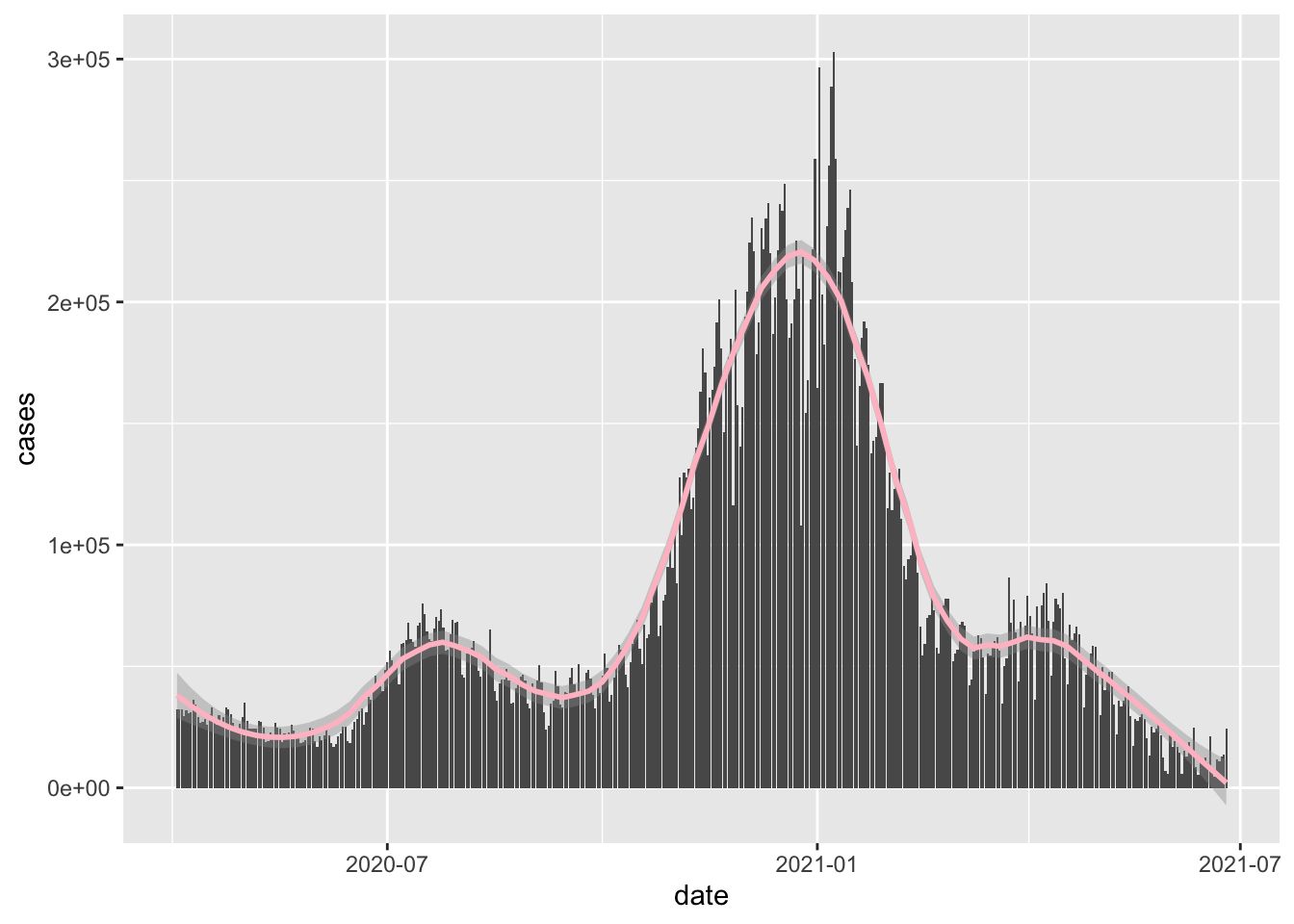

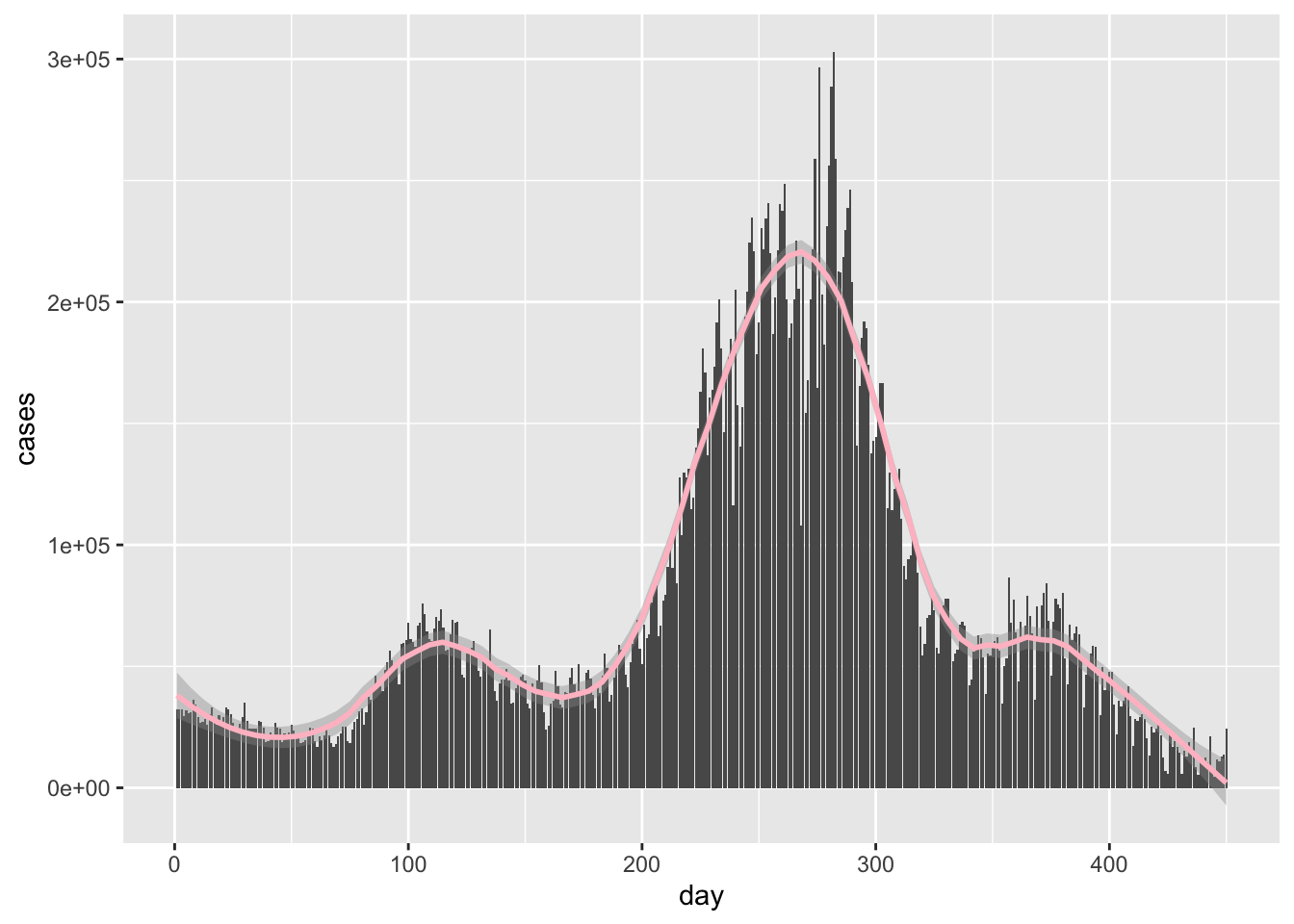

2 Local regression

We can also consider methods for building curves that approximate functions locally.This means for a particular point x, my approximation ˆf(x) is based on points within a neighborhood Br(x)=[x−r,x+r] of radius r centered at x.

More precisely, given a dataset D={(x1,y1),…,(xd,yd)}, my estimated function takes the form

ˆf(x)=1|Ax(r)|∑i∈Ax(r)yi

where Ax is the set of indices such that i∈Ax means that xi is an x-coordinate in the dataset D.

You might notice that smoothing tends to give nicer looking curves than something like polynomial regression. So why every bother with polynomial regression? In short, polynomial regression is a parametrization. At its best, regression builds a model which can be used to predict new data using only a small set of parameters, or numbers that describe my model.

Here is a thought experiment for illustrating the utility of using parameters. Suppose you want to calculate the height h(t) of a ball after dropping it from a tower.

There are three ways to obtain this curve:

Begin with a theory of constant acceleration and derive position, and test against experiment.

Take observations of the falling object and perform a quadratic regression

Perform local averaging with the same data as in (2)

Method (1) is good because it gives us an explanation for our curve based on a simple assumption. Such an assumption can be used to try explaining other phenomena. Method (2) provides us with approximate constants for h(t), but regression doesn’t give us a satisfying explanation for what’s going on. Local averaging is very nice because it can be applied to basically any curve, but its predictive power is clunky at best. One would have to store the entire dataset to ensure a prediction if we have a new datapoint.

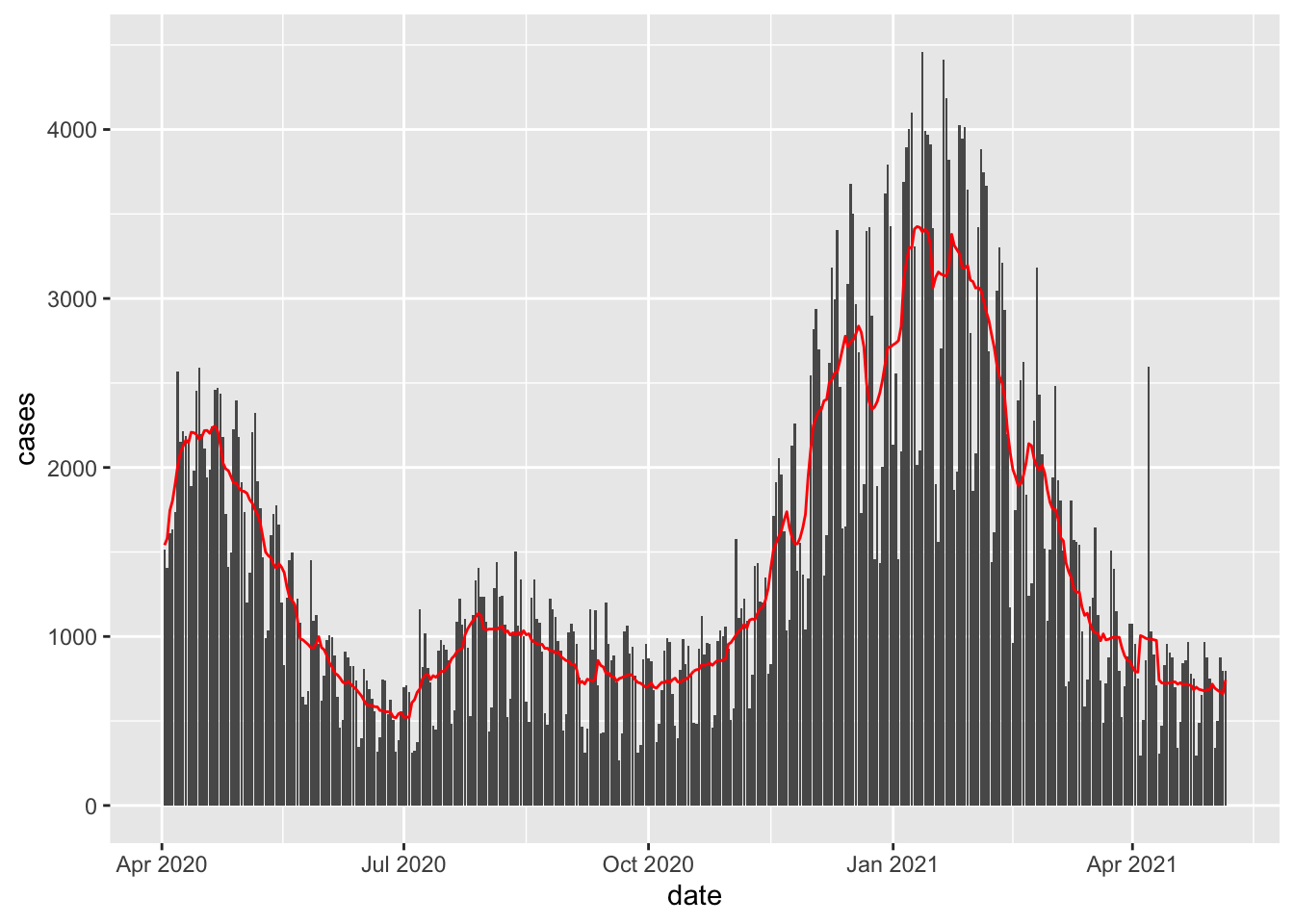

newcor = coronavirus %>% filter(country %in% c("US")

& type == 'death'& date %in% as.Date(1:400, origin="2020-04-01"))

newcor$day = 1:dim(newcor)[1]

span <- 7

#Box Kernel

fit <- ksmooth(newcor$date, newcor$cases,

kernel = "box", bandwidth = span, n.points = dim(newcor)[1])

# #Normal Kernel

# fit <- ksmooth(newcor$date, newcor$cases,

# kernel = "normal", bandwidth = span, n.points = dim(newcor)[1])

newcor %>% mutate(smooth = fit$y) %>%

ggplot(aes(date, cases)) +

geom_bar( stat = 'identity') +

geom_line(aes(date, smooth), color="red")

Q: This certainly beats the polynomial regression models! Why would we ever bother with polynomial regression?

No, I don’t mean this from the perspective of a cheerleader.↩︎

Hideous as expected.

Hideous as expected.