- 1 The mean

- 2 The standard deviation

- 3 Big Theorem 1: the law of large numbers

- 3.1 Law of large numbers with coin flips

- 4 Tracking LLN

- 5 The Cauchy distribution: ruining it for everybody

- 6 The central limit theorem

- 6.1 Generating samples and samples of samples

- 7 The CDF

- 7.1 The Glivenko Cantelli theorem

- 8 The cdf and quantiles in practice

Mean, variance, and the two major theorems in probability

For some random variable X, it’s desirable to be able to describe its main features. For instance, what does a typical sample look like? Also, if we sample a bunch of times, should I expect samples to be very close to eachother, or do samples vary drastically? The two main quantities to answers these questions are the mean and variance. While the mean and variance are quantities related to a random quantity X, they are both deterministic , meaning that they are not random. In most cases, one could think of these quantities as the two most informative numbers describing a random variable.

Q: Note the qualifier ``in most cases” in the last sentence. Can you think of a case where there is a more important quantity related to a random variable? For instance, think of a case where a maximum value of X would be important.

Not only are the mean and variance of great practical value, but they are also at the center of two major theorems in probability: the law of large number and central limit theorem. These two theorems tell us how sums of many random variables act like, and play a vital role in statistics.

1 The mean

For a continuous random variable X with pdf fX, the expected value (or mean) is given by

E[X]=∫∞−∞fX(s)⋅sds

Q: Notice the factor of s next to fX. What would the integral equal if that factor wasn’t there?

For the discrete case, if px=P(X=x), then E[X]=∑x∈S(X)xpx,

We won’t be computing many theoretical means in this class (you’ll be doing plenty of that in a probability class), but it’s a good idea to go through two basic cases:

(Expected value of Bernoulli) For the Bernoulli random variable Bp, the state space is S={0,1}, so then the expected value is

E[Bp]=∑x∈S(X)xpx=1∑0xpx=0⋅p0+1⋅p1=0(1−p)+1(p)=p

(Expected value of Uniform) For the uniform random variable

U(a,b), the state space is S=[a,b] and the pdf if pU(x)=1/(b−a)x∈[a,b]

E[U(a,b)]=∫baxpU(x)dx=∫bax/(b−a)dx=1b−a∫baxdx=1b−a⋅b2−a22=a+b2

Q: Sanity check: without computing anything, why does this answer make sense?

Here’s a sampling-based interpretation of E[X]: if I generate many, many

instances of my random variable X1,X2,…,XN for some very large N, then for most random

variables, E[X]≈(X1+X2+⋯+XN)/N.

In other words, a sample average of N samples of my random variable should approximately give the expected value. So E[X] is an average value of X.

Given a fair coin, how many tails should we expect to flip before we obtain our first heads? The answer is simply E[G.5]. By our definition, since S={0,1,2,…,},

E[G.5]=∞∑0px⋅x=∞∑0(1−p)x⋅p⋅x

This takes some effort to compute (it involves knowledge of geometric series and the binomial theorem). But we can numerically compute the mean just by taking many samples and finding the sample mean:

numsamps = 10000

p = .5

samps = rgeom(numsamps, p)

mean(samps)## [1] 1.0068We can guess that, on average, we will flip one tail before obtaining

our first head. If we need more confidence about that statement, we can

always ramp up the number of samples. The greatest confidence, of

course, is to compute exactly the expected value. The explicit

expression is E[Gp]=1−pp

Q: Another sanity check: without computing anything, as p increases, should the expected value increase or decrease?

Let’s verify that the mean of a standard normal Z0,1 is 0. The expected value is given by

E[Z(0,1)]=∫∞−∞x1√2πe−x2/2

Q: This integral looks pretty awful, but there are at least two quick ways to show that the integral is zero. What are they?

Even without knowing how to compute the integral, we can still show that it’s at least very close to zero via sampling:

numsamps = 10000

samps = rnorm(numsamps, 0,1)

mean(samps)## [1] 0.0027102682 The standard deviation

On average, how far away is a sample X away from its mean? This is what the variance measures. Formally

Var(X)=E[(X−E[X])2]

Formulas abound…we won’t get into them (if you take probability, on the other hand…). The main observation is that Var(X) is an expected value of the squared distance from the mean value to a sample of X.

Q: Think of an extremely boring case of where X=17. No randomness at all. Every time you sample, you get 17. From the definitions above, compute E[X] and Var(X) and the explain why your answers are reasonable.

The standard deviation is simply given by σX=√Var(X)

The upshot for using the standard deviation is that σX has the same units as X (if X is measured in inches, then so is σX.)

We will be using the sd function to compute the sample standard deviation of a finite collection of samples. The formula is quite ugly, but it’s easy to find the definition in a textbook or online. Again, we’re avoiding the weeds here (for the millionth time, take probability and statistics!)

Let’s compute some sample standard deviations:

- Standard Normal

numsamps = 10000

samps = rnorm(numsamps, 0,1)

sd(samps)## [1] 1.001845- Geometric

numsamps = 10000

p = .5

samps = rgeom(numsamps, p)

sd(samps)## [1] 1.401472- Uniform

numsamps = 10000

a = 4

b = 6

samps = runif(numsamps, a,b)

sd(samps)## [1] 0.5806143Q: What happens to the standard deviation of Z0,b as b→∞? What about Za,1 as a→∞? What about Gp as p→0? p→1?

3 Big Theorem 1: the law of large numbers

The law of large numbers is a very formal way of saying “It all comes out in the wash.” Sampling a random variable many times will typically generate a few odd looking individual samples. But with mathematical certainty, there is a 100% probability that if we keep sampling, then we are guaranteed that sample means will converge to the expected value (if there is an expected value).

3.1 Law of large numbers with coin flips

Let N>0 be a large integer, and B1.5,B2.5,…,BN.5 a collection of N Bernoulli random variables with p=1/2. We also need to assume these random variables are independent, meaning that the result of one doesn’t affect the result of another (…there’s a rigorous definition of this). So, if there’s a 50% chance that each Bi.5 is equal to 1, and there’s a 50% chance that it’s equal to 0, then we should expect that

N∑i=1Bi.5/N=(B1.5+…,BN.5)/N≈E[B.5]=1/2

In general, we will be dealing with iid sample X1,…,XN (iid stands __i__ndenpendent and __i__dentically __d__istributed, meaning each sample is being generated from the same distribution). Here are two versions of the law of large numbers:

(Weak LLN)limn→∞P(|ˉXn−μX|>ε)=0.

(Strong LLN) P(limn→∞ˉXn=μX)=1

Notice the location of the limit in each of these expressions. Weak LLN states that sample paths of ˉXn will increasingly land in an ε-tube around μX, while strong LLN says that with probability one a sample path with enter the ε-tube and never leave for all eternity! Given that we’re dealing with random quantities, this is quite the strong statement!

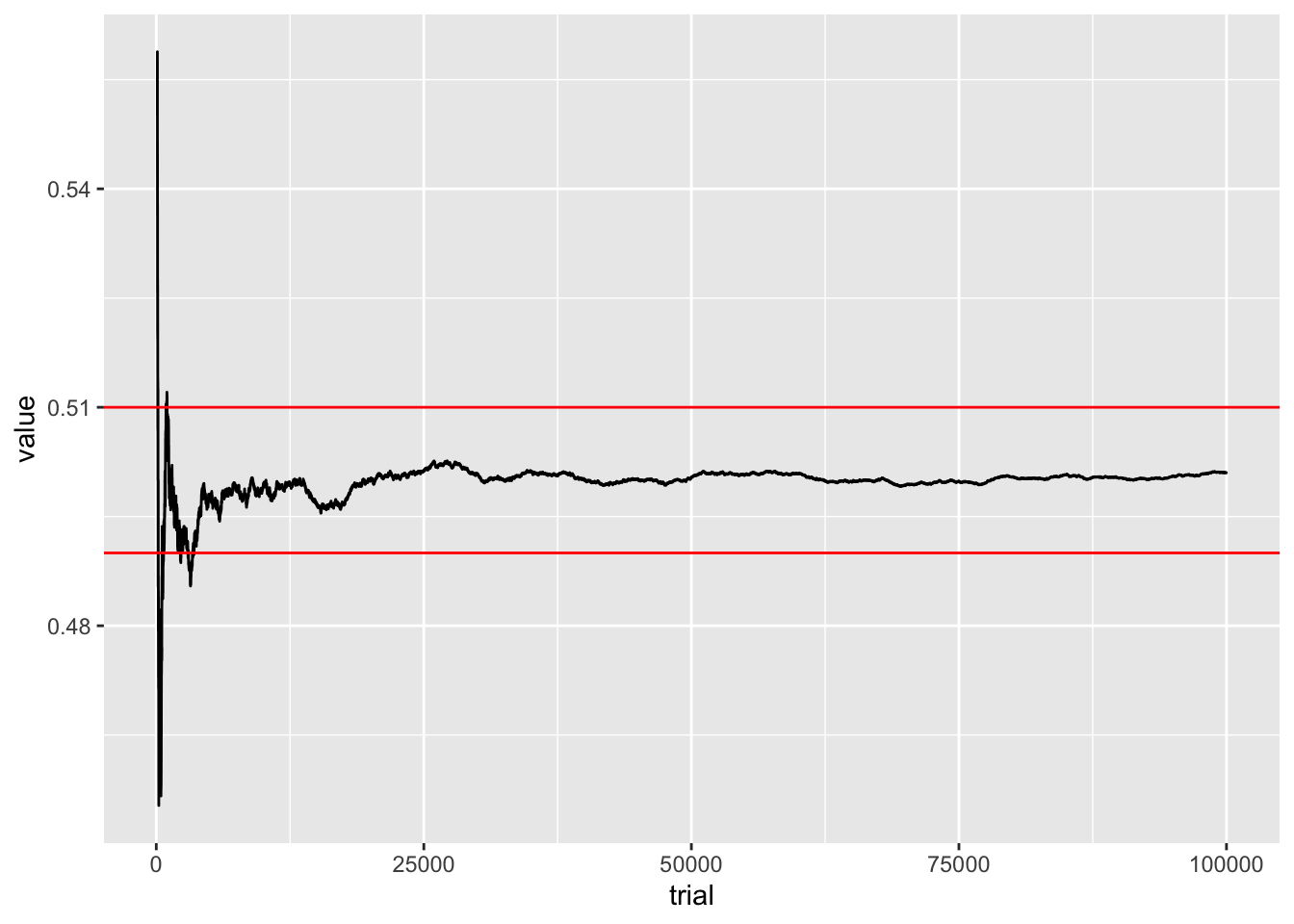

4 Tracking LLN

#Creating an epsilon jail for coin flips

eps = .01

samps = rbinom(100000, 1, .5)

Xbar = cumsum(samps)/1:length(samps)

Xbar = data.frame(Xbar[100:100000])

Xbar$trial = 100:100000

colnames(Xbar) = c('value', 'trial')

Xbar %>% ggplot() + geom_line(aes(trial,value)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = .5 +eps, color = 'red') +

geom_hline(yintercept = .5 -eps, color = 'red') > Q: Is this plot demonstrating the weak or strong

law of large numbers? What would a plot for the other case look

like?

> Q: Is this plot demonstrating the weak or strong

law of large numbers? What would a plot for the other case look

like?

Generate 10000 samples of B.5.

Plot a bar graph for the proportion of each sample.

Write a function that returns SN for N≥1

Plot a line graph the on the x-axis is N and the y-axis is SN. Report on what you find.

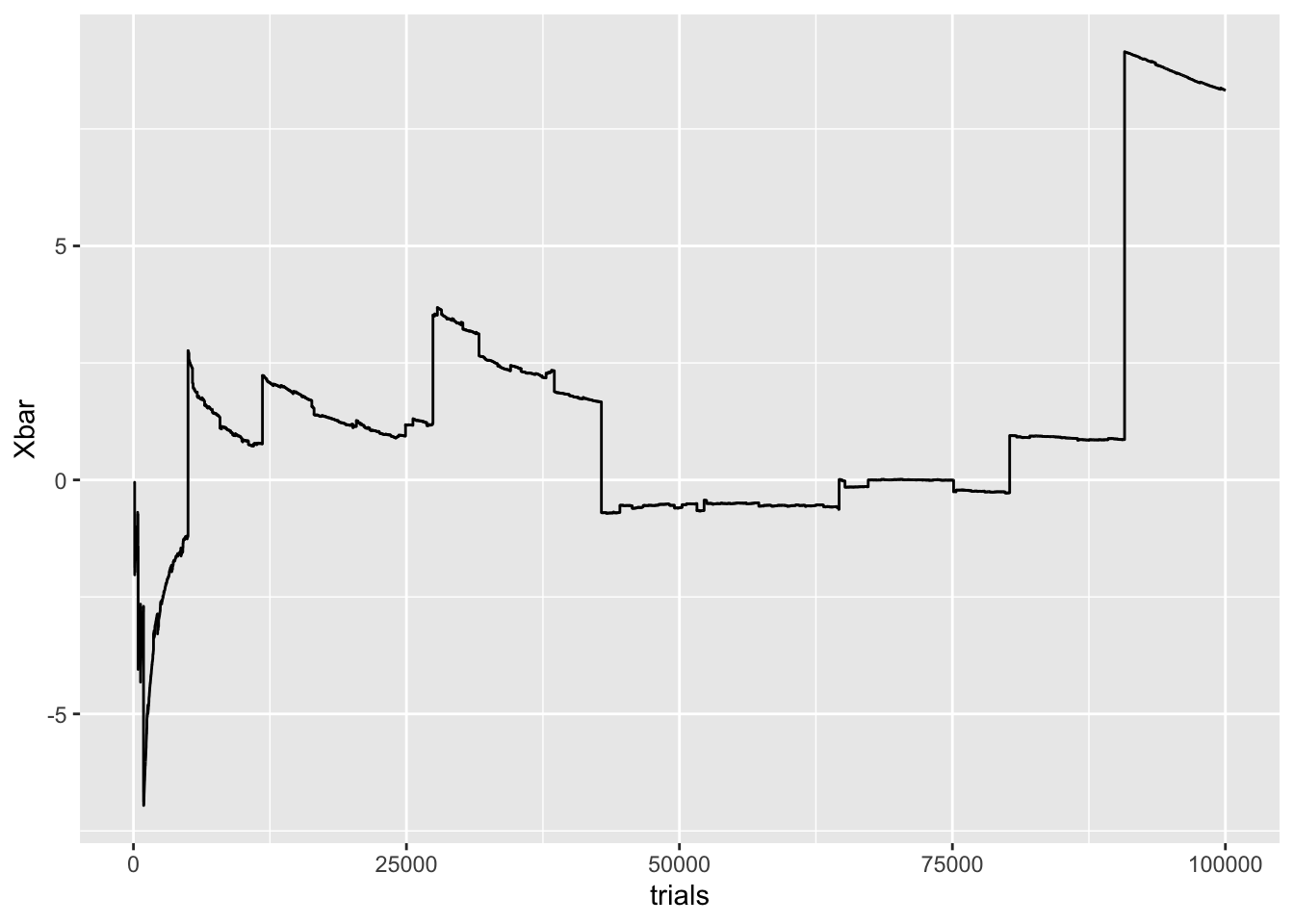

5 The Cauchy distribution: ruining it for everybody

For this exercise, we simulate the royal pain in the neck known as the Cauchy random variable C. It has a PDF of

f(x)=1π11+x2

You can generate a Cauchy random variable by dividing two independent Z0,1 normal random variables. In probability speak,

C∼Z10,1/Z20,1

The Cauchy C random variable is

a problem child. It’s a continuous random variable defined on whole line

with a pdf of f(x)=1π11+x2

Q: What is the integral corresponding to the expected value? Show that the integral doesn’t exist!

If E[C] doesn’t exist, then the law of large numbers doesn’t apply. This means that we’re lost, in general, with regards to what happens to sample means. In terms of the ϵ-prison, the Cauchy distribution is able to make a jail break:

Despite being so unruly, it’s not hard to generate Cauchy random

variables. One way is to simply divide two standard normals Z1,Z2. In probability speak, C∼Z10,1/Z20,1

Let’s repeat the same experiment that we just did with the normal.

runs = 100000

eps = .01

samps = rnorm(runs, 0, 1)/rnorm(runs, 0, 1)

trials = 100:runs

Xbar = cumsum(samps)/1:length(samps)

Xbar = Xbar[100:runs]

C = data.frame(trials, Xbar)

C %>% ggplot() + geom_line(aes(trials, Xbar))

You can see here the result of fat tails. A pdf for a Gaussian collapses to zero incredibly quickly, at a rate of e−x2. Cauchy pdfs, on the other hand, really take their time, decaying at a rate of 1/x2. Since the tails of a Cauchy are so fat, it isn’t insanely rare to draw a sample with an incredibly large magnitude. In the graph above, this corresponds to the big jumps. After each big jump, the sample mean tends to drift toward zero, but inevitably, a devastatingly large sample will be drawn, and ruin everything.

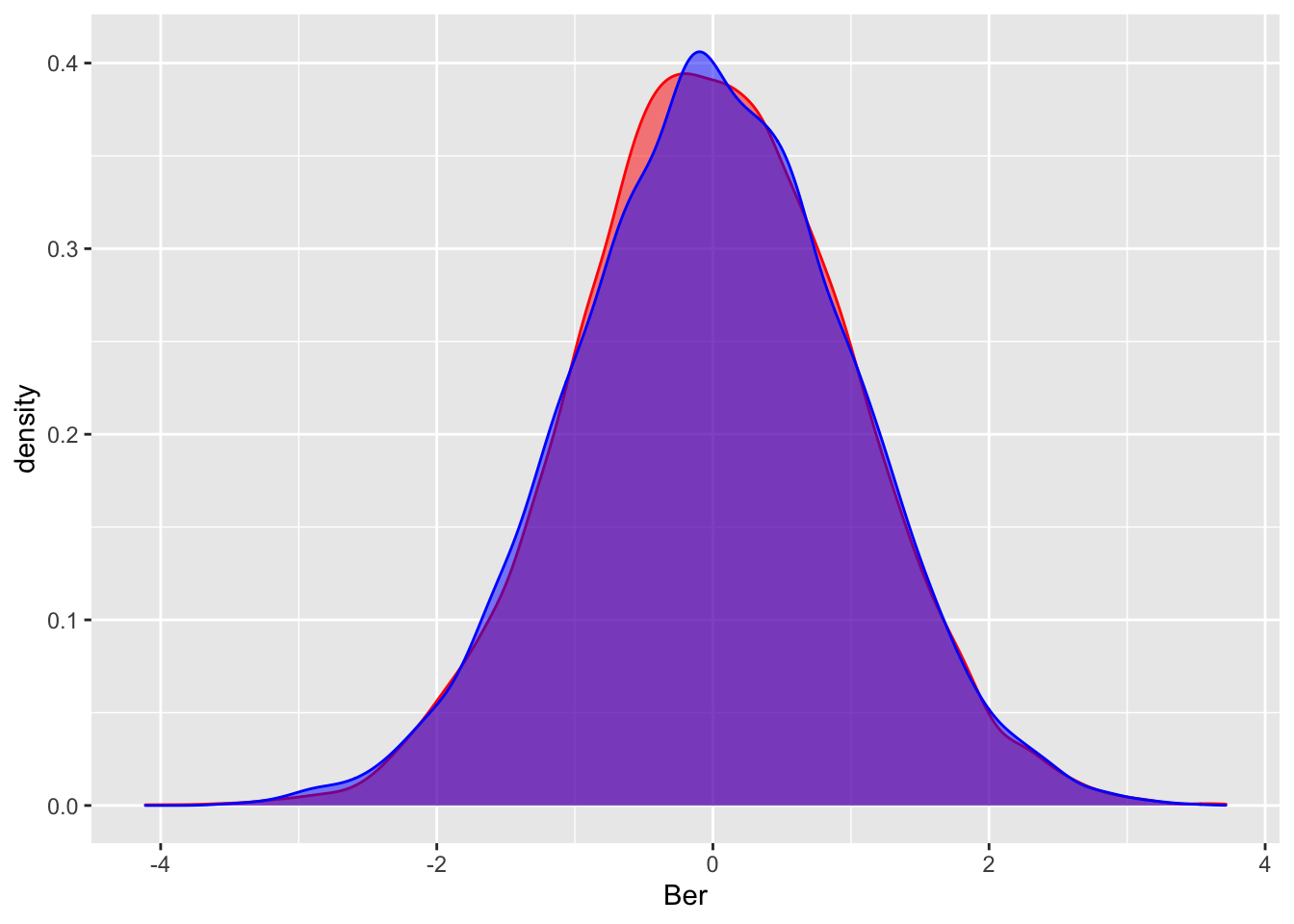

6 The central limit theorem

Perhaps the crown jewel of probability is the central limit theorem. This theorem shows that the normal distribution is, in a sense, universal. This theorem states that for (almost) every random variable, we can take average in the right way and obtain the distribution for Z0,1. That’s quite crazy, since our original distribution can be completely different from a normal. Its pdf can be arbitrarily weird looking. Heck, it could even be a discrete distribution!

So what’s the correct way to take averages? Note that if I take

averages like in the last section, ˉXN=(X1+⋯+XN)/N→E[X].

Sn−nE[X]√nVar(X)→N(0,1)

in law (meaning the histograms of the left and right side ought to look the same for large n).

6.1 Generating samples and samples of samples

We’ll be assuming here that we can generate as much data as we need. The main theme in statistics is scarcity: in reality this is never the case.

Here’s a run through for creating a visual which shows the central

limit theorem. There’s some subtlety here: we are looking at the random

variable T=Sn−nE[X]√nVar(X)

experiments = 10000

flips = 1000

p = .2

A = rep(0, experiments)

for (i in 1:experiments){

A[i] = sum(rbinom(flips, 1, p))

}

meanber = function(p){

return(p)

}

sdber = function(p){

return(sqrt(p*(1-p)))

}

stdize = function(x){

return ((x-meanber(p)*flips)/(sdber(p)*sqrt(flips)))

}

stdizeA = mapply(stdize, A)

#Let's ggplotize this

CLT = data.frame(Ber = stdizeA, Norm = rnorm(experiments, 0, 1))

CLT %>% ggplot()+ geom_density(aes(Ber), fill = "red", alpha = 0.5, bins = 120, color = 'red')+

geom_density(aes(Norm), fill = "blue", alpha = 0.5, bins = 120, color = 'blue')## Warning: Ignoring unknown parameters: bins

## Warning: Ignoring unknown parameters: bins

(Sn−nE[X1])/(√nσX)→Z0,1as n→∞.

To put the CLT in less formal terms:

- Take any random variable X

- Sample it many, many times, and take its sum. Call it Sn

- Chop off the mean of Sn, and divide by the standard deviation of Sn.

- The variable you’re left with should be pretty close to a Z0,1 random variable.

I mean, that’s nice and all, but what does this have to do with data science? Isn’t this a data science class? Well, the point is that if we want to make statements about sample means, then we might deal with things like confidence intervals that use the central limit theorem in a very important way. We’ll visit this shorty.

7 The CDF

One last type of object from probability that we’ll cover is the

cumulative distribution function, or

CDF. Both discrete and continuous random variables have

CDFs. The CDF FX(x) for a random

variable X is defined by FX(x)=P(X≤x).

Q: From this definition, for any X, what should FX(x) be as x→−∞ and x→∞?

For a dataset with values X1,X2,…,XN, there is also the empirical cumulative

distribution function (eCDF), given by ˆFN(x)=#{Xi≤x}/N

In words, this is fraction of Xi which are at most x.

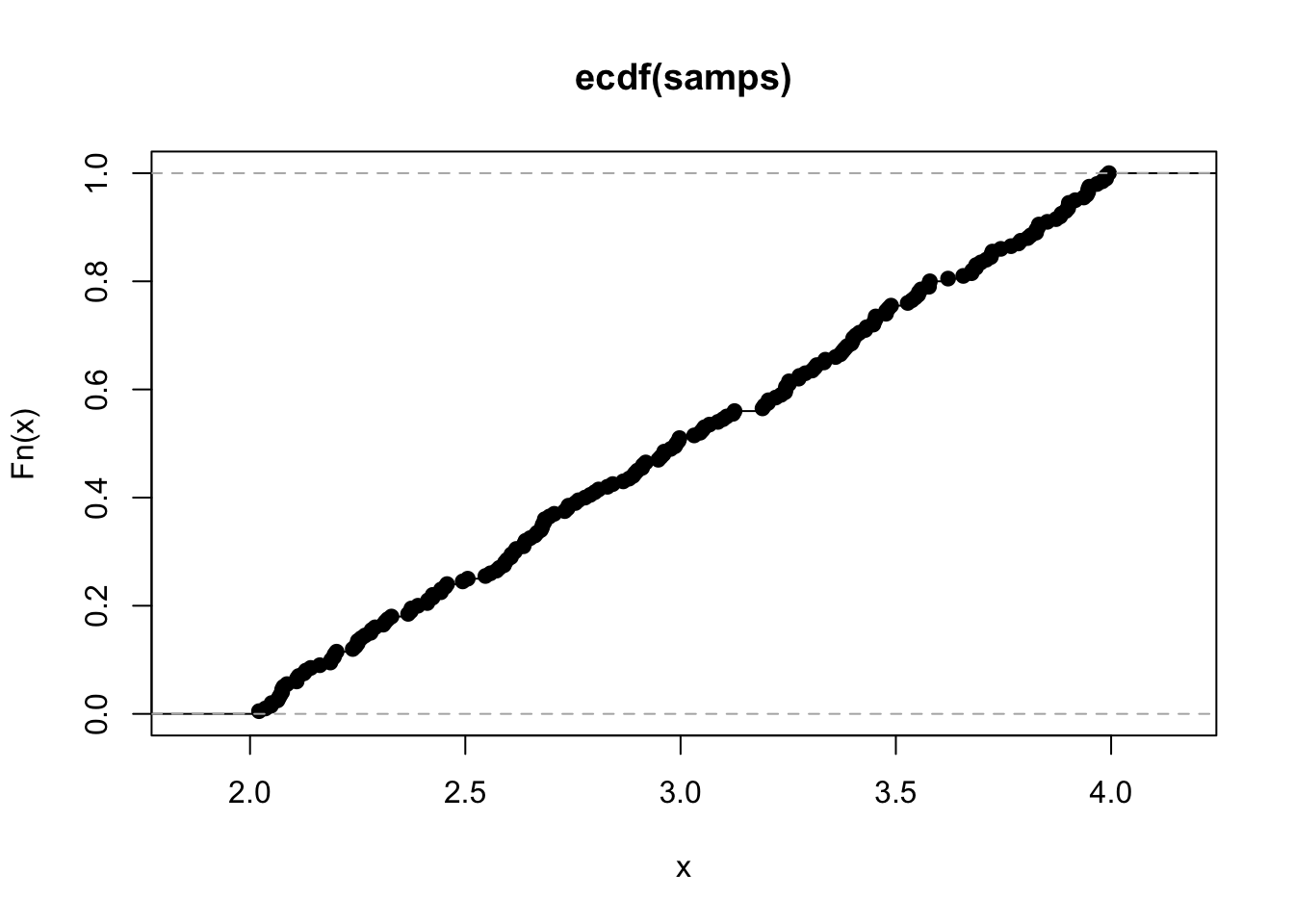

7.1 The Glivenko Cantelli theorem

The Glivenko Cantelli theorem shows that the eCDF approaches the CDF as the number of samples becomes large:

supx|F(x)−ˆFN(x)|→0, as N→∞

Some comments are in order for this equation. It’s okay to think of the expression sup (read “supremum”) as a maximum. What are we taking a maximum of? Well, the biggest absolute difference between the two functions F(x) and ˆF(x). This quantity above is called the Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance between F and ˆFN.

What should the CDF of the Bernoulli random variable B.5 look like?

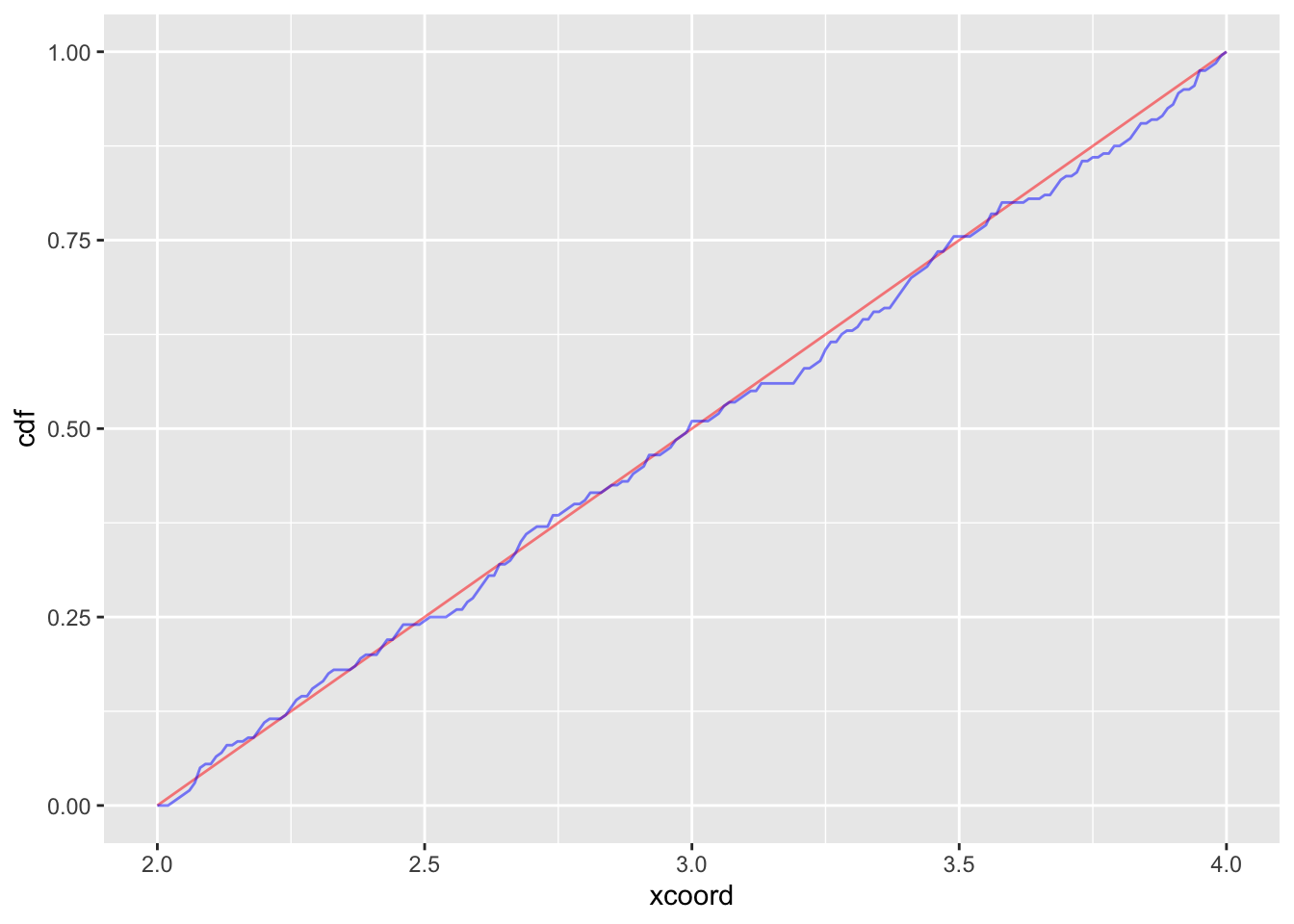

Let’s generate 10000 samples of a Uniform(2,4) random variable. Plot the empirical CDF with the function.

samps = runif(200, 2, 4)

ourbincdf = ecdf(samps)

plot(ourbincdf)

#Compare to cdf of Bernoulli (it's vectorized!)

graphs = data.frame(ecdf = ourbincdf(200:400/100), cdf = punif( 200:400/100, 2, 4), xcoord = 200:400/100)

#Let's just use the alpha argument

graphs %>% ggplot(aes(x = xcoord))+geom_line(aes(y = cdf), color = "red", alpha = .5)+ geom_line(aes(y = ecdf), color = "blue", alpha = .5)

This result holds in general: If I sample many times from some distribution, and take the empirical CDF, it should look very close to the theoretical CDF. This is the Glivenko Cantelli theorem.

Q: What the approximate KS distance between the cdf and ecdf here?

8 The cdf and quantiles in practice

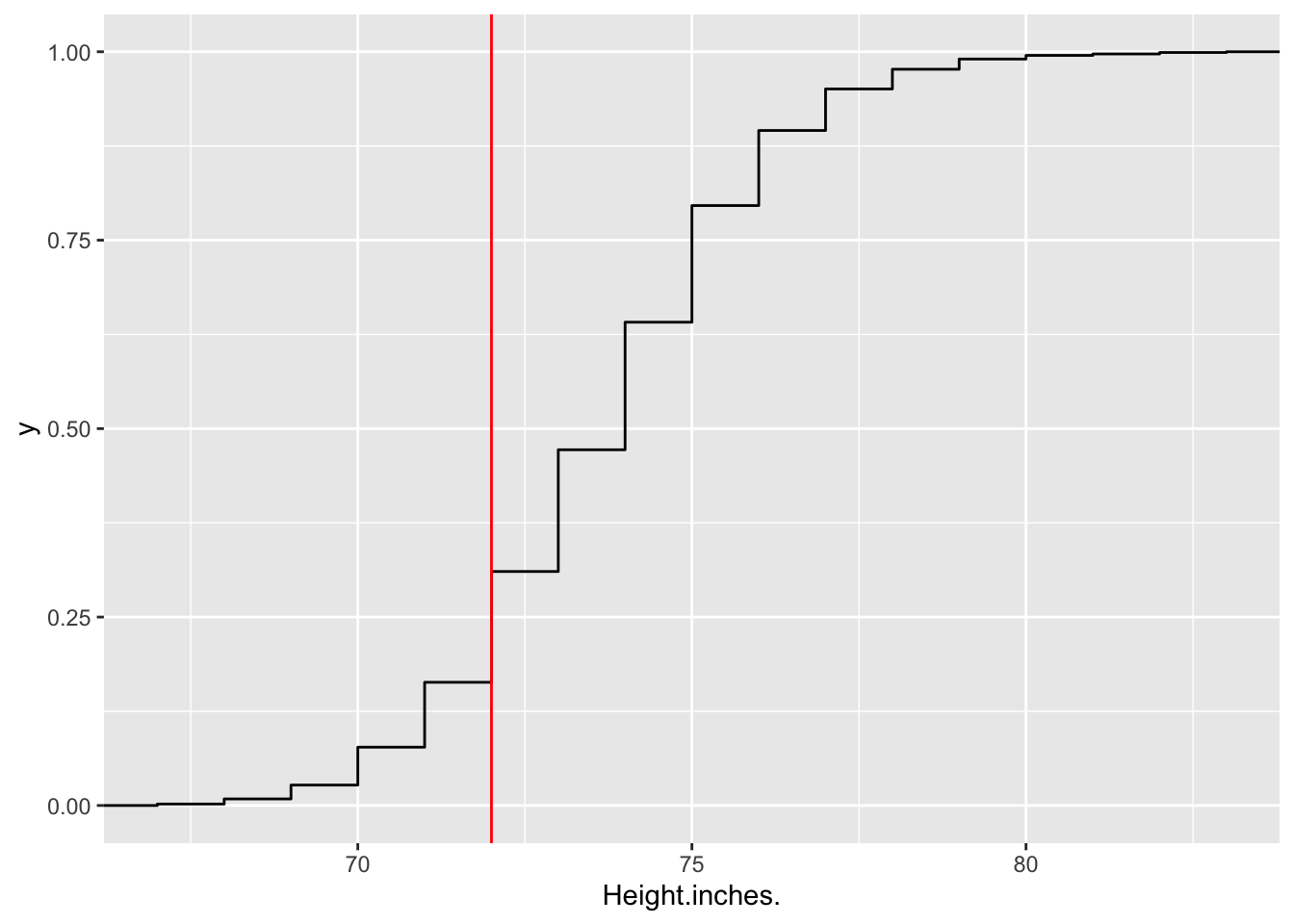

eCDFs can be quite practical when using actual datasets. In this example We will be using the dataset baseball the dataset, which gives positions and physical characteristics of different baseball players.

Let’s ask the following question: What percentage of baseball players are at least 6 feet tall?

Here is the eCDF of heights for different baseball players, along with a vertical line denoting the 6 foot mark:

empcdfheight = ecdf(baseball$Height.inches)

baseball %>% ggplot(aes(Height.inches.))+ stat_ecdf()+

geom_vline(xintercept = 72, color = 'red')

Q: Is the percentage of baseball players over 6 feet more or less than 75%? Be careful! Use the definition of eCDF, or just invoke the fact that CDFs and eCDFs are cadlag (meaning continuous from the right, and having a limit from the left).

As you can see, having an eCDF enables the reader to answer the question “What percentage of players are over/under x inches tall?” for any value of x.

You can in fact just use the ecdf function to answer this question.

empcdfheight = ecdf(baseball$Height.inches)

empcdfheight(72)## [1] 0.3104449Q: What percentage of players are under 75 inches tall? What percentage are at least 70 inches tall?

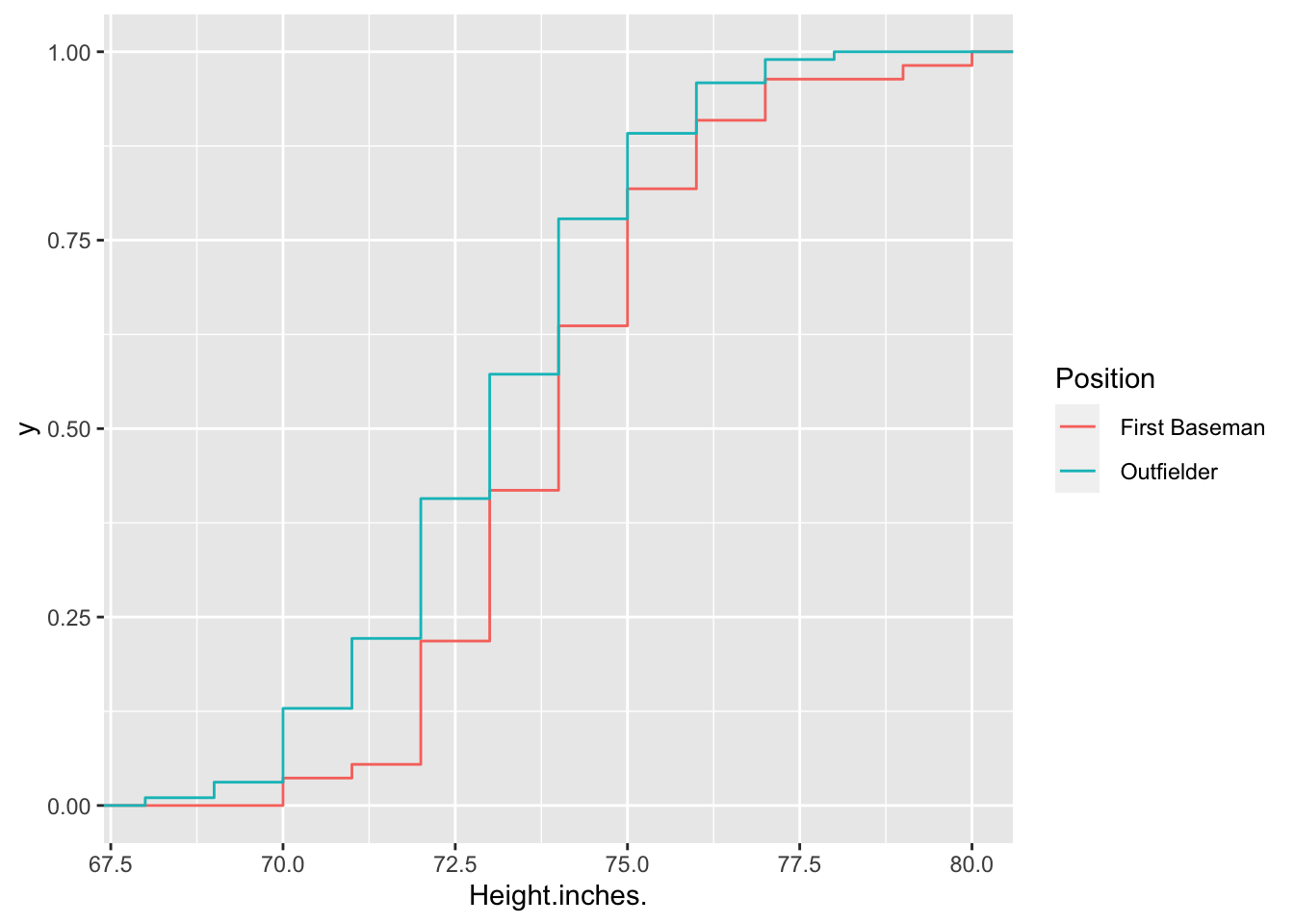

We can further check out individual ecdfs under different positions:

baseball %>% filter(Position %in% c(' First Baseman', ' Outfielder')) %>%

ggplot(aes(Height.inches., color = Position))+

stat_ecdf()

Q: The eCDF for Outfielders is heigher than the eCDF for First Basemen. What does this tell you about comparing heights between the two positions? In fancy probability speak, if the CDF of X is greater than the CDF of Y, we say that Y is stochastically dominant to X.

We can also switch inputs and outputs and ask the question “What value of x is in the pth percentile of the dataset”. This kind of question comes up all the time in standardized testing: “What score do I need to achieve to be at least as good as 90% of all test takers?”. The answer to this question is known as the quantile. It should be seen as the inverse function of the CDF (or eCDF), although there are a few technical issues when trying to take the inverse of a function which has piecewise constant parts. The quantile is given by the R function, quantile (surprise!). The first argument takes in the data and the second corresponds to the percentile.

quantile(baseball$Height.inches., .1)## 10%

## 71quantile(baseball$Height.inches., .9)## 90%

## 77empcdfheight(71)## [1] 0.1634429empcdfheight(77)## [1] 0.950677Q: Hold on! Shouldn’t these values be equal? What happened? Hint: try plugging in values of the empirical cdf at 70.9 and 76.9.

#A universal random variable generator

Besides their use in ranking, quantiles have an incredibly practical purpose. Given a random variable X and a CDF FX(x), we can simulate X by using the quantile function F−1(q) and a run of the mill U(0,1) random number generator. For R, this is simply given by the function runif(1).

How does it work? Well, the theorem is

This theorem states that I can just compose the quantile with a uniform random 1 variable to generate random samples of X.

Proof of claim: (handwavy) We show that F−1X(U) and X have the same CDFs. Let FY be the CDF of F−1X(U)

FY(x)=P(F−1X(U)≤x)=P(U≤FX(x))=FX(x)

…and we’re done!

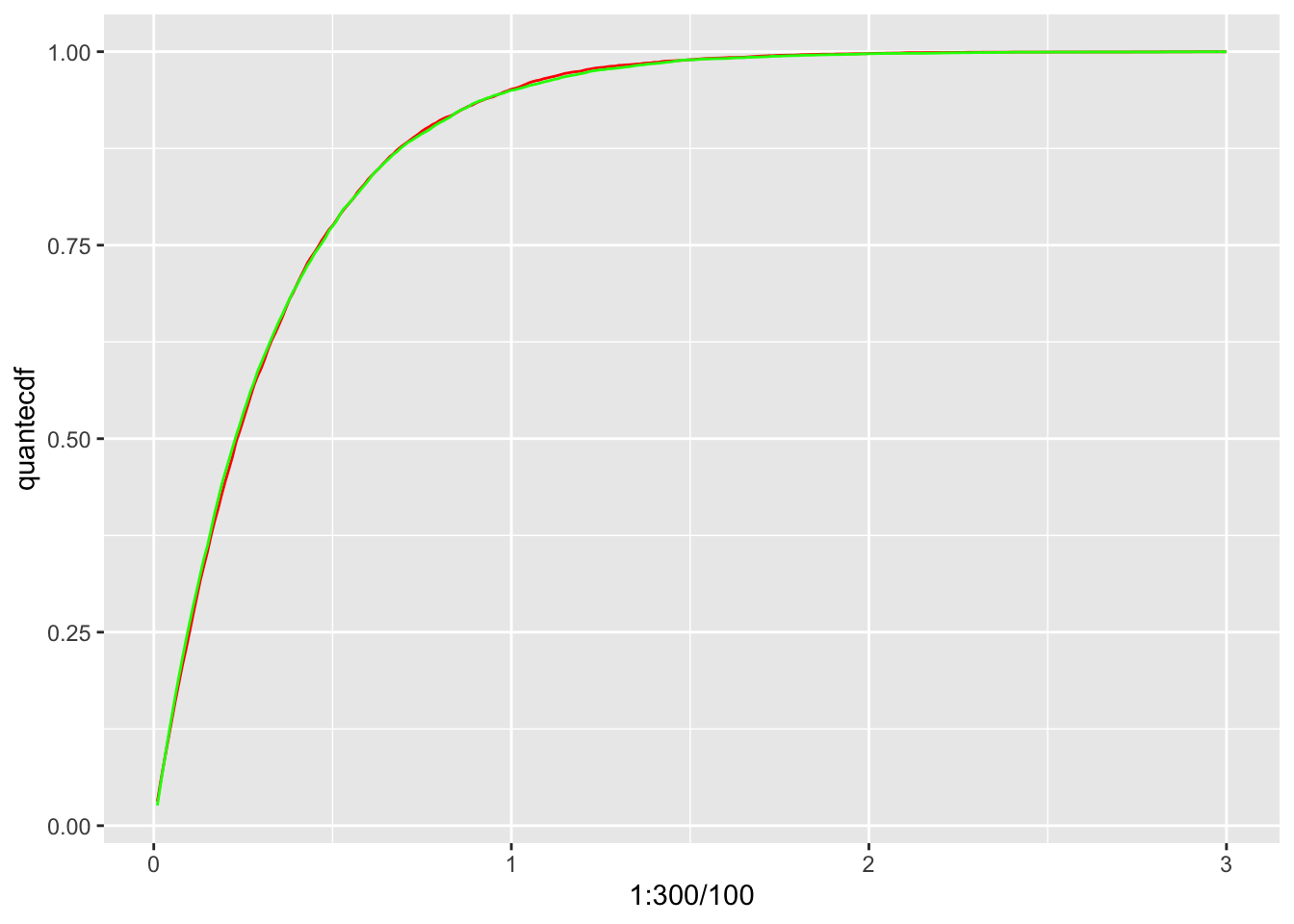

Let’s test this out.

- Derive the quantile for the exponential distribution Xλ where λ=3.

The cdf of an exponential RV is

F(x)=1−e−λx.

The inverse of this function is

F−1(q)=−log(1−q)/λ

Let’s code this up as

lambda = 3

quantexp = function(x){

return(- log(1-x)/lambda)

}- Simulate 10000 samples using the quantile method.

samps = 10000

U = runif(samps)

quantsamps = quantexp(U)- Simulate 10000 samples using the built in R function for exponential random variables.

easysamps = rexp(10000, rate = 3)- Plot the eCDFs of both methods.

quantecdf = ecdf(quantsamps)(1:300/100)

easyecdf = ecdf(easysamps)(1:300/100)

CDFs = data.frame(quantecdf, easyecdf)

CDFs %>% ggplot(aes(x = 1:300/100)) + geom_line(aes(y = quantecdf), color = 'red')+

geom_line(aes(y = easyecdf), color = 'green')

Not bad!